I graduated from high school in June 1978, and a few months later, I joined the Aurora (IL) Police Department as a cadet. In Illinois, police departments can hire people under the age of twenty-one to become cadets, which prepares them to become police officers. At the time, I was eighteen years old, immature, and had no real direction in my life. I needed to figure out what I was going to do for a living, and being a police officer seemed like a reasonable career path to follow.

I graduated from high school in June 1978, and a few months later, I joined the Aurora (IL) Police Department as a cadet. In Illinois, police departments can hire people under the age of twenty-one to become cadets, which prepares them to become police officers. At the time, I was eighteen years old, immature, and had no real direction in my life. I needed to figure out what I was going to do for a living, and being a police officer seemed like a reasonable career path to follow.

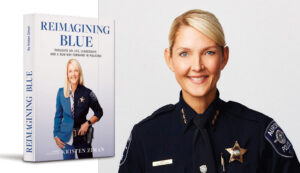

Thirteen years after I joined the police department, Kristen Ziman became a cadet in Aurora. Unlike me, Kristen knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life. Her father was a police officer in Aurora, and she wanted to follow in his footsteps. And while I gave up on becoming a police officer, Kristen followed through, finishing her time as a cadet, became a police officer, moved up the ranks within the department, and eventually became the first female chief in the history of the Aurora Police Department.

I did not know Kristen, but I knew a lot of the same people she knew. I worked with her dad, Hans Kjendal-Olsen, an immigrant from Norway and former US Marine. Hans was always very nice to me. I remember him as a quiet man, a bit of a loner, who I always saw as a bit exotic because of his hyphenated last name. He was the first man I’d ever met with a hyphenated last name (I was not particularly worldly).

I also knew Mike Nila, a fellow police officer and one of Kristen’s main mentors. Mike unknowingly influenced my decision to quit the police department and instead go to college. For Kristen, Mike encouraged her to read widely and seek further education in her chosen profession. Mike had a profound impact on us both.

After Kristen retired as Police Chief in Aurora in 2021, she wrote Reimaging Blue: Thoughts on Life, Leadership, and a New Way Forward in Policing. The book is part memoir, part treatise on what it means to be a cop in modern day America, and part leadership lesson. I’m not exactly sure what I expected when I picked up Reimaging Blue, but I can say that it was much better written, much more interesting, and much more inspiring than I could have expected.

After Kristen retired as Police Chief in Aurora in 2021, she wrote Reimaging Blue: Thoughts on Life, Leadership, and a New Way Forward in Policing. The book is part memoir, part treatise on what it means to be a cop in modern day America, and part leadership lesson. I’m not exactly sure what I expected when I picked up Reimaging Blue, but I can say that it was much better written, much more interesting, and much more inspiring than I could have expected.

Kristen opens the book by recounting what must have been the worst day of her professional career, the mass shooting at Henry Pratt Company, where six people—including the shooter—were killed, and six people—including five police officers—were injured. In Ziman’s telling, the shooting comes to life. As I read, I could feel my pulse quickening and my heart racing.

The book has several police stories, but it’s much more than just memories of her time as a cop . Ziman shares personal anecdotes including stories about her dad’s drinking problems, her marriage to and divorce from a fellow police officer, and her coming to terms with her own sexual orientation. One of the things I appreciated so much about Ziman’s book is the rawness of her story, how she takes responsibility for many of the challenges she faced, and what she learned by dealing with those challenges.

I came to know about Ziman following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. I was sickened when I saw Floyd murdered by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, and my disgust was multiplied when I started reading comments from other police officers defending Chauvin or excusing his behavior.

Kristen Ziman was not one of those cops. In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, she wrote on her Facebook page:

“When I first watched the video of the Minneapolis police officer, I didn’t need to wait for more information to come in. I didn’t need to wait for the investigation to conclude before I made an assessment. When you place your knee on the neck of a human being for over eight minutes—a human being who is handcuffed and pleading that he can’t breathe—there is no defense…Resisting suffocation is not resisting arrest.”

Although I didn’t know Ziman personally, I sensed a kindred spirit who saw the job of police officers in much the same way I did. Ziman saw cops as community defenders and community builders. Without a doubt, she is a supporter of law enforcement officers, who she views as doing a noble and necessary job. However, she sees big problems with the warrior mentality a lot of cops exhibit. While far too many cops view their jobs with an “us against them” mentality, Ziman says there is only “we.” She advocates a police-servant mentality, building relationships in the community and being a good, respectful, and dependable neighbor.

Let me put a finer point on Ziman’s approach to policing. She has no time for cops who abuse their power or use their position for personal gain. She is a tireless promoter of the profession, but she understands that in many communities, police are not always welcome. She supports a more compassionate approach to policing that builds a partnership with the communities being served.

One thing that has impressed me about Ziman is the way the people she leads willingly and happily follow her. She really didn’t discuss this in the book, but I have seen it from afar. Ziman is a petit female in a profession dominated by macho males. Yet, she rose to the level of chief of her department on her own merits despite the obstacles that were thrown at her along the way.

For Ziman, “leadership is about aligning a vision and taking people where they need to go but otherwise wouldn’t. It’s about setting clear goals for your people and getting work done through others.” This is pretty standard stuff, but it’s foundational to being a leader.

When Ziman attended a three-week course at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, she learned another definition of leadership from Prof. Marty Linksy. Linsky suggested that leadership is about disappointing people at the rate they can absorb. Initially, Ziman rejected the idea. Disappointing people? Isn’t leadership about building people up, motivating and encouraging them? What was Linsky talking about?

Ziman left Harvard not understanding Linsky’s message. But when she got back to her office and had time to reflect on what her professor had said, she had a light bulb moment. As she describes in the book:

“When you are the top person in an organization, you can no longer point to someone above you and shift responsibility. That means that every decision is yours and yours alone. And even if you’ve collected other opinions and data, and made an informed decision, it’s still not going to please everyone. Even with the best of intentions, a leader is going to upset someone. Whether it be through a policy decision, a choice for promotion, or administering discipline, leaders disappoint people. Even when attempting to implement something new and big, that will change an organization for the better, people resist because it’s different from what they are used to. People are creatures of habit and they don’t particularly like to be forced out of their comfort zones. When their environment shifts, they stand their ground in defense of it…Being a leader who actually transforms an organization invariably means that some people are going to get left behind. It also means that you (the leader) have to find the precise amount of transformation, because people who walk in and decide to scrap everything are making a mistake. Every organization has a lot of wonderful in it, and those things should be left exactly as they are. But the things that need to be changed should be changed, even if it means that people are going to be disappointed in the process.”

Weeks after reading Reimaging Blue, I continue to be struck by the stories told and the lessons shared by Ziman. She shared them with authenticity, competence, hard-earned wisdom, and compassion. And she offered them in a way that is extraordinarily accessible to the reader.

Ziman is a young woman who, despite being retired, has much still to offer the police profession. I don’t know what the future holds for her, but I suspect she will play a leadership role in transforming another police department or law enforcement organization in the same way she transformed the Aurora Police Department.

Reimagining Blue is an informative, entertaining read that can be enjoyed by anyone. For law enforcement officers—particularly those in leadership positions—Ziman’s book should be required reading.

Is the United States on the verge of Civil War 2.0? The answer is…well, complicated. Let me explain.

Is the United States on the verge of Civil War 2.0? The answer is…well, complicated. Let me explain. I’m in the mood to write a couple thousand words about one of my favorite sports, IndyCar racing. This past week, the IndyCar series announced their 2023 schedule, and it got me thinking about what I would like to see change with the schedule. I love the series, but I’ve never understood why their season ends so early every year. This year, for instance, the final race of the season is on September 11, a full two months or more before most American-based motorsports series end.

I’m in the mood to write a couple thousand words about one of my favorite sports, IndyCar racing. This past week, the IndyCar series announced their 2023 schedule, and it got me thinking about what I would like to see change with the schedule. I love the series, but I’ve never understood why their season ends so early every year. This year, for instance, the final race of the season is on September 11, a full two months or more before most American-based motorsports series end. The other night, the Cubs were on Sunday Night Baseball on ESPN playing the Giants. I was looking forward to watching the game because earlier this year, I gave up my MLB.TV subscription and had not seen many Cubs games. But when game time approached, I decided not to watch the game. I just couldn’t do it. Watching the Cubs this year has been too depressing, and I wasn’t in the mood to be depressed again. As it turned out, the Cubs lost the game 4-0 and, from reports I read after the game, they played just as badly as I feared.

The other night, the Cubs were on Sunday Night Baseball on ESPN playing the Giants. I was looking forward to watching the game because earlier this year, I gave up my MLB.TV subscription and had not seen many Cubs games. But when game time approached, I decided not to watch the game. I just couldn’t do it. Watching the Cubs this year has been too depressing, and I wasn’t in the mood to be depressed again. As it turned out, the Cubs lost the game 4-0 and, from reports I read after the game, they played just as badly as I feared. It isn’t much to look at. It’s not ugly, but there’s nothing beautiful about it either. It’s just an old barn. Gray, weathered boards cover the exterior, along with a few mismatched sheets of unpainted brown plywood here and there covering holes in the walls. The roof is covered with gray corrugated steel, the edges rusty and worn.

It isn’t much to look at. It’s not ugly, but there’s nothing beautiful about it either. It’s just an old barn. Gray, weathered boards cover the exterior, along with a few mismatched sheets of unpainted brown plywood here and there covering holes in the walls. The roof is covered with gray corrugated steel, the edges rusty and worn.

Want to be a better person?

Want to be a better person? If you read

If you read  Later this week, I’ll be traveling to Macomb, IL to finish something I started in 1984.

Later this week, I’ll be traveling to Macomb, IL to finish something I started in 1984. THE STORY

THE STORY