Back in January 2021, in the days following the insurrection at the Capitol, I read an article by David French entitled “Only the Church Can Truly Defeat a Christian Insurrection.” I was a little shocked by the title. Did someone think the insurrection had anything to do with Christianity? If they did, I assumed they must be a militant atheist, quick to blame the church for every ill suffered by society. But when I read the article, my mind was opened to a world I previously didn’t know existed.

Back in January 2021, in the days following the insurrection at the Capitol, I read an article by David French entitled “Only the Church Can Truly Defeat a Christian Insurrection.” I was a little shocked by the title. Did someone think the insurrection had anything to do with Christianity? If they did, I assumed they must be a militant atheist, quick to blame the church for every ill suffered by society. But when I read the article, my mind was opened to a world I previously didn’t know existed.

Let me start by telling you about the author, David French. French is a conservative Christian and a former attorney who argued several high-profile religious liberty cases. He wasn’t the atheist I assumed him to be. In fact, he was just the opposite, a Christian who had dedicated his life and his legal practice to defending the rights and liberties of his fellow Christians. So, why was he seemingly laying blame for the insurrection at the feet of Christians?

French answered that question by describing what he and others saw at the Capitol on January 6, 2021:

“Why do I say this was a Christian insurrection? Because so very many of the protesters told us they were Christian, as loudly and clearly as they could…I saw much of it with my own eyes. There was a giant wooden cross outside the Capitol. ‘Jesus saves’ signs and other Christian signs were sprinkled through the crowd. I watched a man carry a Christian flag into an evacuated legislative chamber…Christian music was blaring from the loudspeakers late in the afternoon of the takeover. And don’t forget, this attack occurred days after the so-called Jericho March, an event explicitly filled with Christian-nationalist rhetoric so unhinged that I warned on December 13 that it embodied “a form of fanaticism that can lead to deadly violence.”

Did you catch the term he used to describe the rhetoric being used by the insurrectionists? “Christian-nationalist.” French wasn’t blaming Christians writ large for the insurrection, but a small group of what he called “Christian Nationalists.” It was a term I was not familiar with.

So, what is Christian Nationalism? Unfortunately, French didn’t provide a neat and tidy definition in his article, but he did give a hint. He compared Christian Nationalists to Islamic terrorists. He writes:

“Are you still not convinced that it’s fair to call this a Christian insurrection? I would bet that most of my readers would instantly label the exact same event Islamic terrorism if Islamic symbols filled the crowd, if Islamic music played in the loudspeakers, and if members of the crowd shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’ as they charged the Capitol.”

I understood French’s point, but I have to admit that blaming Christians—even a sub-group of Christians—for the insurrection made me a little uncomfortable. True, I have my own issues with the church, but until then, I had never thought of any group of Christians as violent, anti-American insurrectionists. It seemed to me that what the insurrectionists wanted—in a nutshell, the end of democracy and the rolling back of rights—was actually anti-Christian. Why would Christians fight for what I considered anti-Christian?

I had a lot of questions, the most basic of which was finding a good definition for the term Christian Nationalist. I did a lot of reading, and most writers danced around an actual definition, instead pointing to what people they viewed as Christian Nationalists said or did. The most helpful definition I found came from Wikipedia.

“Christian nationalists believe that the US is meant to be a Christian nation and want to ‘take back’ the US for God. Experts say that Christian-associated support for right-wing politicians and social policies, such as legislation related to immigration, gun control and poverty is best understood as Christian nationalism, rather than as evangelicalism per se. Some studies of white evangelicals show that, among people who self-identify as evangelical Christians, the more they attend church, the more they pray, and the more they read the Bible, the less support they have for nationalist (though not socially conservative) policies. Non-nationalistic evangelicals agree ideologically with Christian nationalists in areas such as patriarchal policies, gender roles, and sexuality.”

British author and economist Umair Haque, a keen observer of American politics, had a less clinical definition of Christian Nationalism:

“Maybe, it’s a hard one to even get your head around. What is “Christian Nationalism”? And how should Americans — and Westerners beyond America’s shores, because this movement is spreading — think about it? After all, you don’t have to think too hard to grasp that Jesus hardly proclaimed many of the things this movement believes in. He would have been repelled by many such things, like this pretty good summary:

‘As a political theology that co-opts Christian narratives and symbolism, Christian nationalism has its own version of the ‘elect,’ those chosen by God. They are ‘people like us,’ meaning conservative Christian, but also white, natural-born citizens. Moreover, in a prosperous nation, only ‘the elect’ should control the political process while others must be closely scrutinized, discouraged, or even denied access. This ideology is fundamentally a threat to a pluralistic, democratic society.”

This was a good base to draw from, but I still didn’t completely understand Christian Nationalists or what they wanted for the United States. What I needed was a backstory, a way to understand where the Christian Nationalists belief system came from. Put another way, I needed to understand why Christian Nationalists believe what they believe. As it turns out, their belief system begins with the founding of our nation.

Christian Nationalists believe that the United States was conceived as a Christian nation and that the Founding Fathers were guided by the hand of God in crafting the Constitution. Because of this, they want to bring an end to the separation of church and state, and as a God-inspired document, believe the Constitution should not be altered or amended.

There’s a lot to unpack here. Let’s start with the notion that the United States was conceived as a Christian nation.

Diana Butler Bass, author and historian of Christianity, has written extensively on this idea that the United States was founded as a Christian country. “That the United States is not a Christian nation should be obvious because no nation has ever been a Christian nation — not even the political state of the Vatican! And there’s never been a truly Christian nation. Ever.”

Bass goes on to explain that, while the United States was shaped by Christianity, it certainly was never a Christian nation. This is an important distinction. The United States was founded by people who held strong Christian beliefs, who held beliefs from other religions, as well as no religion at all. Christian beliefs and values helped shape the Constitution as well as life in the early days of our nation. But the Constitution,–particularly the First Amendment– makes it abundantly clear that the founders did not conceive of our new nation as a Christian nation.

Next, let’s consider the claim that our Founding Fathers were guided by the hand of God when writing the Constitution. If you’ve been watching the January 6 hearings, you likely are familiar with Rusty Bowers, the Republican Speaker of the Arizona State Legislature. Bowers was called before the January 6 Committee because, after losing the 2022 election, Donald Trump contacted him asking for his help in overturning the results of the vote in Arizona.

Bowers testified that he refused Trump’s request because he felt what he was being asked to do flew in the face of the Constitution. He said that he could never defy the Constitution because he believed that, like the Bible, the United States Constitution was divinely inspired. Not only would defying it go against the oath he took to defend and uphold the Constitution, it would also be a betrayal of his most deeply held Christian beliefs.

This type of deification of the Founding Fathers has always chafed me. The Founding Fathers were a mixed group of men, all with certain strengths and weaknesses. They did not all hold to the same ideas about the type of nation the United States should be, and they certainly did not agree with one another when it came to religion. The Constitution is the product of a diverse and often divided committee that did the best they could. They were an imperfect group that crafted a very good, but imperfect document.

One example of how imperfect the men and the document are is the fact that it does not, in the first three words of the preamble—“We the people”—include African Americans, who at the time of the writing of the Constitution, were being held as slaves. In fact, several of the Founding Fathers were slaveholders.

Now, are you going to make the case that God, in his infinite wisdom, wanted Black people to be slaves? Does Rusty Bowers and others like him truly believe that the God they worship, the one they refer to when they claim “God is love,” divinely inspired the Founding Fathers to institutionalize slavery in the Constitution?

We do a disservice to the Founding Fathers when we make them out to be anything other than men of their time. They were farmers and diplomats and merchants and soldiers. They were not vessels of the almighty. They were just men, in many ways common and flawed, who did what they thought was right at the time. We should remember that when we endeavor to raise them up on a pedestal and elevate them above their fellow man.

Perhaps the most flawed doctrine of Christian Nationalism is the idea that, as a Christian nation, we should end the separation of church and state, and that the Constitution should not be amended. Let’s start with the first half of that claim.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution says in part:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Ironically, the earliest Americans believed there should be a separation between church and state for the sake of the church. They did not want the government meddling in the affairs of the church.

Roger Williams was a former Protestant chaplain who turned to Puritanism for his spiritual sustenance. However, he found himself clashing with the Puritan leaders and was eventually banished from Massachusetts. He later founded Rhode Island and is credited with being the first person to use the phrase “separation of church and state.”

Williams believed that an authentic Christian church could only survive if there was “a wall or hedge of separation” between the “wilderness of the world” and “the garden of the church.” Williams feared that any government involvement in the religious practices of individuals would ultimately poison and corrupt the church.

Thomas Jefferson supported Williams position, claiming in a speech to the Danbury Baptist Association that, in the first words of the First Amendment, often referred to as the Establishment Clause, the people had agreed to “a wall of separation between the church and state.”

Christian Nationalists calling for that “wall of separation” to be torn down seem to be at cross purposes with many of the Founding Fathers. Instead, they appear to be in lockstep with the Islamic terrorists who carried out the attack on 9/11. Those terrorists wanted a government controlled by the church. But instead of the Christian church, the terrorists wanted the Muslim church to be in charge. And, instead of Biblical principles being used to create laws, the terrorists wanted Sharia Law, based on the Quran. The religion and holy book may be different, but the end result is the same.

When it comes to separation of church and state, I always go to a quote from former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor from the case of McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, where she wrote:

“Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?”

Finally, Christian Nationalists who advocate for no alterations or amendments to the Constitution on the grounds that it was divinely inspired and perfect as is seemingly don’t know that the Constitution has already been amended thirty-three times. This includes the first ten amendments, which were agreed to before the Constitution was signed, and which are contained in the Bill of Rights, one of our country’s founding documents.

The idea that the Constitution shouldn’t be amended is also betrayed by the fact that the Founding Fathers included in the Constitution rules for how to amend it. I would argue that those rules are too stringent, but regardless, the rules are still right there in the Constitution. Obviously, the Founding Fathers, who Christian Nationalists claimed were guided by God, felt that the Constitution should be subject to amendment.

In a recent speech, firebrand Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Green bragged about being a Christian Nationalist and encouraged others to join her. She explained that, like others in the audience, she is a strong, unapologetic Christian who loves her country. According to Green, that’s all a Christian Nationalist is: someone who is Christian and loves their country.

Of course, that isn’t all there is to Christian Nationalism. There is a dark undertone to the movement, a desire to rule over the country, control fellow citizens, and a willingness to engage in violence to achieve those goals. There are fascist and authoritarian currents running through the Christian Nationalist movement. Despite their professed love for country and democracy, they work tirelessly to alter country and destroy democracy. They claim to be working toward salvation in the afterlife, but their aims and tactics are clearly rooted in earthly pursuits in the here and now.

I want to return to something Umair Haque said in the quote I mentioned earlier concerning the Christian Nationalist belief that only the “elect,” or “people like us” (white, natural-born, conservative, Christian, and predominately male) should be in charge, or even have a say in the way the government is run. In this sense, Christian Nationalists are not only talking about leadership roles in the government. They are talking about only people like them having the right to vote. This notion is not only undemocratic, but unconstitutional.

As a reminder, here’s what Haque said in part:

“[I]n a prosperous nation, only ‘the elect’ should control the political process while others must be closely scrutinized, discouraged, or even denied access. This ideology is fundamentally a threat to a pluralistic, democratic society.”

This idea that only certain people should qualify as the elect is not new. At the beginning of our country, only white, male, property-owners were given the vote. Except in extremely rare instances, this excluded all women, all blacks and other minorities, as well as non-property-owning white men from having a say in who represented them and ran the government.

It wasn’t until 1828 that non-property-owning white men could vote in federal elections. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment gave black men the right to vote. The Nineteenth Amendment, which passed in 1920, gave all women the right to vote in federal elections. And in 1965, the Voting Rights act passed, protecting everyone’s right to vote.

For much of our country’s history, the most basic element of a democracy—voting—was denied to some citizens. Today, when you hear people like Rep. Lauren Boebert—herself, a Christian Nationalist—refer to “real Americans” or “true patriots,” she is referring to this idea that only certain people—people like her—deserve the right to vote as well as enjoy the other Constitutionally-guaranteed rights and privileges citizens of the United States are entitled to.

So, why is Christian Nationalism seemingly so powerful at the moment. There are a few reasons. First, it is important to recognize that only about twenty-to-twenty-five percent of the population holds views consistent with Christian Nationalism. And even among that group, there is a fall off the more radical the beliefs get.

For instance, as many as twenty-five percent of Americans may hold some beliefs consistent with Christian Nationalism. But if you ask them if they agree that all non-Christians or all non-Republicans (or RINOs) should be jailed, or even killed, much of that twenty-five percent support would erode. The point is, despite the outsized role they play in our politics at the moment, they are far from a majority.

Second, traditionally, Republicans have courted the votes of Christian Nationalists, but they haven’t been willing to invite them all the way into the tent or give them much of a voice in the Party’s platform or policies. That has changed. When Republicans embraced the Tea Party movement in the 1990s and early 2000s, they opened the door to many far-rightwing politicos who held Christian Nationalist beliefs.

That door was kicked in completely when Donald Trump became the nominee of the Republican Party in 2016. Trump brought with him a coalition of Christian nationalists, white supremacists, neo-Nazis, authoritarians, fascist wannabes, conspiracy theorists, and other fringe players that had previously been keep at arm’s length. Rather than staying on the fringe, these people were invited into the tent and given a prominent place in the campaign, and after his election victory, in the administration. No group benefitted from the Trump presidency more than Christian Nationalists.

But it wasn’t just being in the tent with Trump and the Republicans that supercharged Christian Nationalists. Until recently, they didn’t play particularly well with 1930’s style fascists, such as white supremacists and neo-Nazis, or authoritarians, such as plutocrats like Trump and others who seek political control as a way to power and wealth.

For instance, think about this triumvirate in Nazi Germany. Fascists and authoritarians came together under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. Theocrats (the generic name for the group that includes Christian Nationalists) didn’t go along with Hitler’s plans. So, they were shunned, or worse. Even so, with just two of the three groups working together, Hitler was able to take over Germany and much of Europe, and came perilously close to defeating NATO nations in World War II.

Fast forward to today. Things have changed. Intentionally or not, Trump has brought these three groups together. That is extremely bad news for the United States and our democracy.

Here’s how Haque describes the peril we face.

“When theocrats, fascists, and authoritarians form an alliance, it’s really bad news. It points to the most severe form of social collapse on the cards. That is because usually these groups are at loggerheads. They usually don’t all want the same things, because naturally, their perspectives and ‘philosophies’…are opposed. Theocrats believe in divine law and salvation from above, whereas fascists believe in a kind of supremacist biological essentialism. Authoritarians and oligarchs generally don’t want to be bound by theocratic restrictions on business, because they get in the way of making money and keeping power.”

Christian Nationalists believe they are fighting a war between good and evil. I use the word “war” intentionally here. For many (but not all) Christian Nationalists, they believe the only way to save the nation is to execute a violent war against non-believers and anyone who stands in the way of creating a true Christian nation. They often speak of a new civil war, and they glory in the thought of donning the armor of God in preparation for the fight, perhaps shedding blood or even dying in what they view as a righteous holy war. (I previously wrote about the prospects for a new civil war in this post)

This is the part of Christian Nationalism that scares me most. They seem willing—even eager—to die for their cause. In many cases, they are heavily armed and believe that God has called them to fight for his kingdom here on earth. Many Christian Nationalists want blood and war. They want to fight for God against their fellow citizens, who they view as “the enemy.” They are anxious for violence.

Diana Butler Bass recently wrote about this obsession with blood and war among Christian Nationalists, and her conclusion echoes that of David French. If Christian Nationalism is to be stopped, it is up to Christians to stop it.

“One of the possible futures for America is that the unholy trinity of theocrats, fascists, and authoritarians launches their desired Civil War to quench their thirst for blood.

“What can stop this?

“That’s a huge question. And, I suspect, it is also a question that many people and entities far beyond my purview are wrestling with right now. I admit to feeling a certain helplessness when listening to the news — or reading articles like the ones linked to today’s post.

“However, I do know one thing that might help — Christianity itself. Only Christians can finally and fully reject the bloody theology that has so often resulted in calamity and that threatens us now.

“Oddly and rarely, Christianity has risen above its bad blood to achieve its alternative vision of peace with amity. For every violent emperor, bad pope, twisted crusader, and abusive preacher, there have always been protesters, subversives, resisters, truth-tellers, healers, and saints.

“Whenever Christianity practices goodness and justice, it almost always emerged from the latter group — the quiet, the powerless, the prayerful, the questioners, the mystics, the heretics, the wise, and the wanderers. It is a Christianity that leans toward love, afloat in the waters of grace, and not a religion obsessed with blood. It knows that purity is not the point.

“That’s what will help unhinge this madness — risky goodness. Attentiveness to where theology can go awry. The only antidote to theocratic Christianity is the brave, kind, persistent, merciful, and insistent faith that stands with and for human solidarity and comity. We can’t afford blood-soaked religion any more.

“Christians must stand up, speak up, and do good right now. Civil war isn’t funny. We can’t let it happen. We don’t need purity. We need decency. And peaceable community.

“There can be no hedging of bets when other Christians are calling for blood to purify the nation. We must remove the curse of bad blood before it kills us all.”

Bass offers only a tiny glimmer of hope. There isn’t much good to grab onto when it comes to Christian Nationalism and the future they see for America. So, a little hope is a welcome thing. It may not be much, but I’ll take it.

Kurt Vonnegut is an interesting guy. I’ve written about him a couple of times before, and each time I do, I tend to learn something about Vonnegut, something about myself, and above all, something about writing.

Kurt Vonnegut is an interesting guy. I’ve written about him a couple of times before, and each time I do, I tend to learn something about Vonnegut, something about myself, and above all, something about writing.

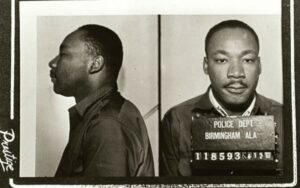

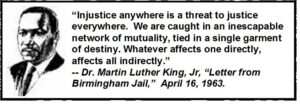

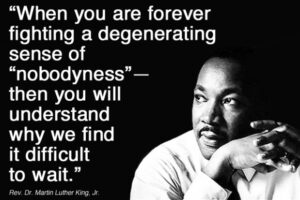

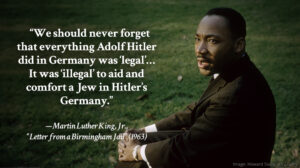

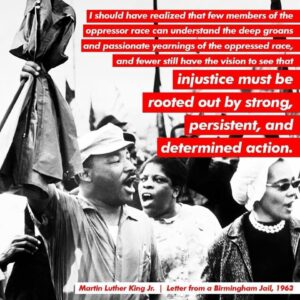

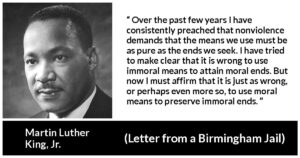

In early April 1963, the civil rights movement, led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and it’s co-founder, Martin Luther King, Jr, seemed to be stalled. Despite non-violent protests across the nation, the Kennedy Administration, which had come to power promising civil rights legislation, had seemingly turned a blind eye. They were still supportive, or so it seemed, but they weren’t doing much to fulfill their promise.

In early April 1963, the civil rights movement, led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and it’s co-founder, Martin Luther King, Jr, seemed to be stalled. Despite non-violent protests across the nation, the Kennedy Administration, which had come to power promising civil rights legislation, had seemingly turned a blind eye. They were still supportive, or so it seemed, but they weren’t doing much to fulfill their promise.

I’m sure you’ve heard it said that for maximum health benefits and weight loss, you should walk 10,000 steps per day. But is that really true? Probably not. In the very least, it’s not based on science.

I’m sure you’ve heard it said that for maximum health benefits and weight loss, you should walk 10,000 steps per day. But is that really true? Probably not. In the very least, it’s not based on science. Chevrolet, Audi, and Dodge have done a masterful job of selling their cars by telling emotionally engaging stories that feature their vehicles, but don’t focus on their vehicles.

Chevrolet, Audi, and Dodge have done a masterful job of selling their cars by telling emotionally engaging stories that feature their vehicles, but don’t focus on their vehicles.  For the past twenty years, I have been associated with

For the past twenty years, I have been associated with

If you’d like to help, I’d encourage you to make a donation to Heart of a Child via Zelle (you can donate to

If you’d like to help, I’d encourage you to make a donation to Heart of a Child via Zelle (you can donate to

If you’ve followed me on Facebook for any time at all, you know of my love for log cabins. Over the years, I have posted a lot of pictures of cabins. At one point a few years ago, my friend, Brett Morley, asked, “Why don’t you just buy one?” I finally have, Brett. I only wish you were here to see it.

If you’ve followed me on Facebook for any time at all, you know of my love for log cabins. Over the years, I have posted a lot of pictures of cabins. At one point a few years ago, my friend, Brett Morley, asked, “Why don’t you just buy one?” I finally have, Brett. I only wish you were here to see it. Back in January 2021, in the days following the insurrection at the Capitol, I read an article by David French entitled “

Back in January 2021, in the days following the insurrection at the Capitol, I read an article by David French entitled “

I am saddened, but not surprised, at the number of people who are screaming “It’s not fair” in response to the recent announcement that the government is going to forgive up to $20,000 of student loan debt for select Americans who currently have a student loan. I suspect that most of the people opposed to student loan forgiveness don’t know the history of student loans, and therefore have based their opinions on emotion or misinformation rather than facts.

I am saddened, but not surprised, at the number of people who are screaming “It’s not fair” in response to the recent announcement that the government is going to forgive up to $20,000 of student loan debt for select Americans who currently have a student loan. I suspect that most of the people opposed to student loan forgiveness don’t know the history of student loans, and therefore have based their opinions on emotion or misinformation rather than facts. I graduated from high school in June 1978, and a few months later, I joined the Aurora (IL) Police Department as a cadet. In Illinois, police departments can hire people under the age of twenty-one to become cadets, which prepares them to become police officers. At the time, I was eighteen years old, immature, and had no real direction in my life. I needed to figure out what I was going to do for a living, and being a police officer seemed like a reasonable career path to follow.

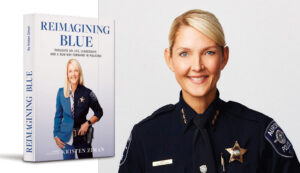

I graduated from high school in June 1978, and a few months later, I joined the Aurora (IL) Police Department as a cadet. In Illinois, police departments can hire people under the age of twenty-one to become cadets, which prepares them to become police officers. At the time, I was eighteen years old, immature, and had no real direction in my life. I needed to figure out what I was going to do for a living, and being a police officer seemed like a reasonable career path to follow. After Kristen retired as Police Chief in Aurora in 2021, she wrote Reimaging Blue: Thoughts on Life, Leadership, and a New Way Forward in Policing. The book is part memoir, part treatise on what it means to be a cop in modern day America, and part leadership lesson. I’m not exactly sure what I expected when I picked up Reimaging Blue, but I can say that it was much better written, much more interesting, and much more inspiring than I could have expected.

After Kristen retired as Police Chief in Aurora in 2021, she wrote Reimaging Blue: Thoughts on Life, Leadership, and a New Way Forward in Policing. The book is part memoir, part treatise on what it means to be a cop in modern day America, and part leadership lesson. I’m not exactly sure what I expected when I picked up Reimaging Blue, but I can say that it was much better written, much more interesting, and much more inspiring than I could have expected.