THE STORY

THE STORY

In September 1864, as the Civil War raged, a widow named Lydia Parker Bixby approached Massachusetts Adjunct General William Schouler and informed him that five of her sons, all serving in the Union Army, had been killed. Schouler was touched by the loss suffered by the widow, and asked Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew to notify the President of Mrs. Bixby’s story and requested that the President send a letter of condolence to her.

Governor Andrew relayed the request to Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War. The Secretary asked Andrew to provide him with the names of Bixby’s sons and the units in which they served. Schouler retrieved the information from Mrs. Bixby and sent it to Secretary Stanton, who then passed the request on to the President.

In addition to requesting the letter, Schouler made an appeal for contributions for the families of soldiers at Thanksgiving. The appeal was published in both the Boston Evening Traveller and the Boston Evening Transcript, and it included information about Mrs. Bixby and the five sons she had lost in the war. A portion of the proceeds from the appeal were delivered to Mrs. Bixby on Thanksgiving Day. The following day, she received the letter of condolence from the President.

A copy of Lincoln’s letter was published in the Boston Evening Transcript. Lincoln’s sincere condolences struck a chord with readers of the letter, and it served to increase his popularity and strengthen the war effort among the people of Boston, and throughout Massachusetts.

THE TRUTH

It’s true that Lydia Parker Bixby spoke to Adjunct General Schouler. What was said between the two is a matter of controversy. Schouler was clear that Bixby claimed her five sons had been killed in the war. Some time later, after receiving the President’s letter, Bixby claimed she never told Schouler five of her sons had died in the war. The truth was, Bixby had lost two sons, not five.

Of the five Bixby sons that served during the war:

- Sargent Charles N. Bixby was killed in action near Fredricksburg, Virginia on May 3, 1863,

- Private Oliver Cromwell Bixby was killed in action on July 30, 1864 near Petersburg, Virginia,

- Private Arthur Edward Bixby deserted his post at Fort Richardson, Virginia on May 28, 1862. He hid out until after the war, then returned to Boston,

- Private George Way Bixby was captured at Petersburg on July 30, 1864 and was held as a POW at Salisbury Prison in North Carolina. Reports differ as to what happened to him after his confinement. One report indicates that he died while in custody at Salisbury. Another indicates he joined Confederate forces and re-joined the fight.

- Corporal Henry Cromwell Bixby was captured by Confederate troops at Gettysburg and was sent to Richmond, Virginia. He was released on March 7, 1864 and subsequently received an honorable discharge.

Astonishingly, the War Department had records for all five Bixby boys, but ignored them, instead relying on Mrs. Bixby’s claims.

The letter from the President that received so much praise throughout Massachusetts seemed not to impress the widow Bixby. In fact, Elizabeth Towers, a granddaughter of Mrs. Bixby, reported that her grandmother was a southern sympathizer who was indignant over the letter. She claimed that Mrs. Bixby had “little good to say about President Lincoln.” It was reported that Mrs. Bixby destroyed the letter after reading it.

The copy of the letter that was given to the Boston Evening Transcript was also destroyed by the newspaper’s editor after it was printed in the paper. Since then, several people have claimed they have copies of the original letter, but the claims have always proved to be forgeries.

Along with the Gettysburg Address and his second inaugural address, the Bixby Letter is considered one of Lincoln’s finest written works. It has been quoted in memorials, included on epitaphs, and was even used in the popular film, Saving Private Ryan.

However, many scholars believe that the letter was not written by Lincoln. They instead attribute the letter’s authorship to John Hay, Lincoln’s assistant private secretary.

Lincoln was incredibly busy during the last few months of 1864, executing the war and trying to keep his cabinet together. It’s very possible that he delegated the task of writing the letter to Hay. However, there is no definitive evidence to support the contention that Hay was the author.

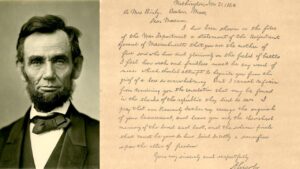

THE LETTER

Here is the letter of condolence that President Lincoln sent to the widow Bixby:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam,–

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln