Politically speaking, I came of age in 1980. That year, I worked on the campaign of presidential candidate John Anderson, an Illinois Congressman who was running as an independent. To be honest, my motives working for the campaign were a bit misdirected. I was chasing a girl who worked on the campaign. Anderson won 6.6% of the vote. I did significantly worse.

Politically speaking, I came of age in 1980. That year, I worked on the campaign of presidential candidate John Anderson, an Illinois Congressman who was running as an independent. To be honest, my motives working for the campaign were a bit misdirected. I was chasing a girl who worked on the campaign. Anderson won 6.6% of the vote. I did significantly worse.

But it wasn’t Anderson that opened my eyes to the world of politics. It was Ronald Reagan. Reagan exuded a positive, can-do attitude that I found contagious. While Democrats seemed to be constantly singing a song of woe, Reagan and the Republicans were singing a song of hope and possibility. For a young guy with his whole life ahead of him, the choice between the two was simple.

At the time, Republicans were the party of ideas. They had a message to move the country forward, to make life better for the average American. While Democrats groused about how bad everything was, Republicans offered positive solutions to the challenges we faced.

My, how things have changed. The script has completely flipped. Today, Republicans spend their time airing their grievances and doing what they can to take the country backwards to a time that exists only in their nostalgic minds. They’ve sold their souls to a reality TV conman who has reduced the once Grand Old Party to a cartel of grifters, conspiracy theorists, and authoritarian wannabes. At the same time, Democrats have become the party of ideas, offering hope and a vision for a brighter future where democracy is maintained and strengthened. The differences between the two parties couldn’t be much more stark.

The term “conservative,” has lost all meaning. When I was a young man growing up in the 1970’s and 80’s, a conservative could be a democrat, and a liberal could be a Republican. Those two terms–conservative and liberal–were not assigned to any one party. As a result, parties came to the table with proposals that worked for all (or most) of their members, and often, for most of the members of the opposing party as well.

Beginning in the 1980’s, liberals gravitated to the Democratic Party and conservatives to the GOP. For a while, it was easy to use the terms “liberal and Democrat,” as well as “conservative and Republican,” interchangeably. It’s still common to associate liberals with the Democratic Party, but where have the conservatives gone?

Today, Republicans—particularly MAGA Republicans—like to refer to themselves as conservative. But despite their claims, the word conservative has a defined meaning. And politics as practiced by Republicans is not conservative.

David Brooks, the New York Times opinion columnist, has a long list of conservative bona fides. For 20 years, Brooks has been the conservative voice at the NYT, and he has been the conscience of the Republican Party. He recently wrote an article in the Atlantic asking the question, what happened to American conservatism? I found his piece enlightening and have excerpted it below. If you’d like to read the entire article, you can find it here.

I thought it would be helpful to treat my interaction with Brooks article as a quasi-conversation in hopes of clarifying and expanding his thoughts. Brooks’ words are italicized. Mine are in normal font.

Brooks: What passes for “conservatism” now…is nearly the opposite of the Burkean (political philosopher Edmund Burke) conservatism I encountered then. Today, what passes for the worldview of “the right” is a set of resentful animosities, a partisan attachment to Donald Trump or Tucker Carlson, a sort of mental brutalism. The rich philosophical perspective that dazzled me then has been reduced to Fox News and voter suppression.

I recently went back and reread the yellowing conservatism books that I have lugged around with me over the decades. I wondered whether I’d be embarrassed or ashamed of them, knowing what conservatism has devolved into. I have to tell you that I wasn’t embarrassed; I was enthralled all over again, and I came away thinking that conservatism is truer and more profound than ever—and that to be a conservative today, you have to oppose much of what the Republican Party has come to stand for.

Mindar: Describing the culture of grievance and cult-like following of people like Donald Trump and Tucker Carlson as “mental brutalism” is apt. Cruelty seems to be the point of most Republican policy, assuming you can actually find Republicans advocating policy positions as opposed to spouting culture war sound bites. They seem to operate from the premise that what is good for the country—and they define “the country” as “us”—is what most hurts their political opponents. It’s this idea that the only thing that matters is owning the libs.

Republicans by and large have turned their backs on intellectualism. They view experts and people who have spent their lives studying a subject as “elites” who should be shunned and their opinions dismissed. Instead, they prefer the opinions of the MAGA everyman, a person or people who have no particular expertise, but who are fellow travelers with a common enemy. That’s how we got to the point on the right of people treating Covid with a horse dewormer.

The ”mental brutalism” also includes a propensity to resort to political violence. When they don’t have the superior argument or the moral underpinning or the requisite number of votes, followers of MAGA believe violence can get them what they want. It is perhaps the most un-conservative belief of this supposedly conservative political party. It is a belief that is far more at home in places like Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea than in modern day America.

Brooks: The most important sentiments are moral sentiments. Conservatism certainly has an acute awareness of sin—selfishness, greed, lust. But conservatives also believe that in the right circumstances, people are motivated by the positive moral emotions—especially sympathy and benevolence, but also admiration, patriotism, charity, and loyalty. These moral sentiments move you to be outraged by cruelty, to care for your neighbor, to feel proper affection for your imperfect country. They motivate you to do the right thing.

Burkean conservatism inspired me because its social vision was not just about laws, budgets, and technocratic plans; its vision was about soulcraft, about how we build institutions that produce good citizens—people who are moderate in their zeal, sympathetic to the marginalized, reliable in their diligence, and willing to sacrifice the private interest for public good. Conservatism resonated with me because it recognized that culture is more important than the state in driving history. “Manners are of more importance than laws,”

Mindar: Like Brooks, I saw conservatism as a philosophy to build a better, kinder, more caring America, I wasn’t blind to the marginalized groups that were being left behind, but I thought a more compassionate conservatism could bring them along. Unfortunately, while I focused on individual bigotry and discrimination, I didn’t realize that institutional racism was so big and so pervasive that, even if we could cure individual citizens of their bigotry through conservatism, institutional racism would continue to weigh the country down. I admit, I was naïve. But I thought at the time that conservatism was the key to helping to lift up the downtrodden and right the discriminatory wrongs of the past.

Unfortunately, what has happened in the past several decades is that Republicans have embraced what Brooks calls the sinful aspects of conservatism—selfishness, greed, lust—mixed in with what passes for patriotism on the right, and have abandoned the more positive aspects of conservatism, such as charity, loyalty, community, and altruism, to create a toxic form of conservativism that worships the worst people, praises the worst attributes, and views the more positive aspects of Burkean conservativism as weak. People who exhibit these more positive aspects are referred to as “woke” or “snowflakes” by MAGA conservatives.

Brooks: Conservatives thus spend a lot of time defending the “little platoon[s],” as Burke called them, the communities and settled villages that are the factories of moral and emotional formation. If, as Burke believed, reason alone cannot find the one true answer to any social problem, each community must improvise its own set of solutions to intricate human concerns. The conservative seeks to defend this wonderful heterogeneity from the forces of bigness and the centralizing arrogance of rationalism—to protect these little platoons when government tries to perform roles best done in families, when the federal government takes power from local government, when big corporations suck the vitality out of local economies.

Mindar: Brooks speaks longingly of the conservative preference for small government. However, I would argue that the zealousness with which Republicans pursued small government (in rhetoric, if not in practice) is what has led to the distrust of governmental institutions necessary for the operation of a democracy. Preference for a small government turned into simple loathing for all government. This has led to today’s Republicans not having any coherent governing philosophy. Though they seek power, they do so for its own sake. They do not have grand plans for an American government that accomplishes anything other than tearing itself apart. They weaponize governmental power to punish their political enemies, even as they claim their political enemies are weaponizing government against them. In Congress, they hold the country hostage through the budget process; they threaten to defund the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the IRS; they say they want to eliminate the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Education, the Department of Energy, and any other department that displeases them. Their rhetoric is more akin to anarchy than conservative governance.

Brooks: True conservatism’s great virtue is that it teaches us to be humble about what we think we know; it gets human nature right, and understands that we are primarily a collection of unconscious processes, deep emotions, and clashing desires. Conservatism’s profound insight is that it’s impossible to build a healthy society strictly on the principle of self-interest. It’s an illusion, as T. S. Eliot put it, to think that a society in which people don’t have to be good can thrive. Life is essentially a moral enterprise, and the health of your community will depend on how well it does moral formation—how well it nurtures ordered inner lives and helps balance sentiments, desires, and motivations. Finally, conservatism welcomes you into a great procession down the ages. Society “is a partnership in all science,” Burke wrote, “a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”

Mindar: This paragraph from Brooks is an excellent example of how far from conservatism Republicans have strayed. Nearly every action they take is designed to prop up their friends and destroy their enemies. There is no sense of community. They are not looking out for the least among us. In fact, they work to accomplish the exact opposite. They do everything they can to further marginalize the already marginalized. They apparently believe that society can thrive through self-interest and power. The health of the community is of no concern to Republicans. Or, to put a slightly finer point on it, they view the community as being made up of only those that believe as they believe. Non-believers are ostracized and excluded from the community. They refer to these non-believers as “not real Americans.” So, in their minds, they continue to care for the community, but the community doesn’t include anyone that doesn’t think like they think.

Brooks: I realized that every worldview has the vices of its virtues. Conservatives are supposed to be epistemologically modest—but in real life, this modesty can turn into a brutish anti-intellectualism, a contempt for learning and expertise. Conservatives are supposed to prize local community—but this orientation can turn into narrow parochialism, can produce xenophobic and racist animosity toward immigrants, a tribal hostility toward outsiders, and a paranoid response when confronted with even a hint of diversity and pluralism. Conservatives are supposed to cherish moral formation—but this emphasis can turn into a rigid and self-righteous moralism, a tendency to see all social change as evidence of moral decline and social menace. Finally, conservatives are supposed to revere the past—but this reverence for what was can turn into an abject deference to whoever holds power.

Mindar: Wow, what a paragraph. I agree with every word. MAGA Republicans have convinced themselves that: 1) Among nations, the United States is exceptional, and 2) Foreigners from lesser countries (some of them “shithole” countries) are overrunning our borders and intend to take our exceptional country away from “true Americans.” This jingoistic (not patriotic) fervor for country coupled with a paranoid hatred for outsiders is a hallmark of MAGA political philosophy. To stray from this doctrine is to have your MAGA card revoked, reduced to the scrap heap of RINOland.

Any mention of a change to policy that would benefit normal working-class folks or, worse yet, marginalized Americans, is met with a knee-jerk reflex among MAGA Republicans to shout “Socialism.” But for MAGA Republicans, “socialism” (along with a host of other words like “woke” and “critical race theory”) is defined as “anything they don’t like or agree with.” In this way, Republicans have ceased to be conservatives, and have instead become reactionaries, opposed to everything, but standing for nothing.

Brooks: American conservatism descends from Burkean conservatism, but is hopped up on steroids and adrenaline. Three features set our conservatism apart from the British and continental kinds. First, the American Revolution. Because that war was fought partly on behalf of abstract liberal ideals and universal principles, the tradition that American conservatism seeks to preserve is liberal. Second, while Burkean conservatism puts a lot of emphasis on stable communities, America, as a nation of immigrants and pioneers, has always emphasized freedom, social mobility, the Horatio Alger myth—the idea that it is possible to transform your condition through hard work. Finally, American conservatives have been more unabashedly devoted to capitalism—and to entrepreneurialism and to business generally—than conservatives almost anywhere else. Perpetual dynamism and creative destruction are big parts of the American tradition that conservatism defends.

Mindar: In this paragraph, Brooks uses the word “liberal” as opposed to illiberal, not as the opposite of conservative. That’s an important point, because American conservatism is wrapped up tightly with the liberal beliefs of individual liberty, equality before the law, political equality and consent of the governed. MAGA Republicans have all but abandoned these principles, instead opting for a more illiberal philosophy that eschews the very values that prompted our forefathers to break away from the crown and strive to form a more perfect union.

Brooks: If you look at the American conservative tradition—which I would say begins with the capitalist part of Hamilton and the localist part of Jefferson; extends through the Whig Party and Abraham Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt; continues with Eisenhower, Goldwater, and Reagan; and ends with Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign—you don’t see people trying to revert to some past glory. Rather, they are attracted to innovation and novelty, smitten with the excitement of new technologies—from Hamilton’s pro-growth industrial policy to Lincoln’s railroad legislation to Reagan’s “Star Wars” defense system.

Mindar: This is what I was talking about before. The Republican Party was once the party of ideas. But as Brooks points out, the linkage between Republicans and conservatism was broken after Mitt Romney’s run for the White House. Donald Trump’s campaign and presidency abandoned conservative principles even while claiming to be the heirs to the American conservative tradition. The fact of the matter is, even while claiming the conservative moniker, Republicans are in many ways, the polar opposite of what has been an American conservative tradition.

Brooks: American conservatism has always been in tension with itself. In its prime—the half century from 1964 to 2012—it was divided among libertarians, religious conservatives, small-town agrarians, urban neoconservatives, foreign-policy hawks, and so on. And for a time, this fractiousness seemed to work.

American conservatives were united, during this era, by their opposition to communism and socialism, to state planning and amoral technocracy. In those days I assumed that this vibrant, forward-looking conservatism was the future, and that the Enoch Powells of the world were the receding roar of a sick reaction. I was wrong. And I confess that I’ve come to wonder if the tension between “America” and “conservatism” is just too great. Maybe it’s impossible to hold together a movement that is both backward-looking and forward-looking, both in love with stability and addicted to change, both go-go materialist and morally rooted. Maybe the postwar American conservatism we all knew—a collection of intellectuals, activists, politicians, journalists, and others aligned with the Republican Party—was just a parenthesis in history, a parenthesis that is now closing.

Mindar: MAGA Republicans have jettisoned intellectuals and credible journalists from their coalition, leaving them with only activists and the politicians who are willing to cow to those activists in order to get re-elected. It is an incestuous relationship that guarantees a dearth of new (or good) ideas, but plenty of ideas that are cruel, illiberal, and destructive of democracy.

Brooks: Donald Trump is the near-opposite of the Burkean conservatism I’ve described here. How did a movement built on sympathy and wisdom lead to a man who possesses neither? How did a movement that put such importance on the moral formation of the individual end up elevating an unashamed moral degenerate? How did a movement built on an image of society as a complex organism give rise to the simplistic dichotomies of manipulative populism? How did a movement based on respect for the wisdom of the past end up with Trump’s authoritarian campaign boast “I alone can fix it,” perhaps the least conservative sentence it is possible to utter?

Mindar: All good and legitimate questions. Trumpism is in many ways the opposite of conservativism. So, why have so many former conservatives been willing to not only tolerate, but in many cases, embrace and advocate for Trumpism?

Brooks: The reasons conservatism devolved into Trumpism are many. First, race. Conservatism makes sense only when it is trying to preserve social conditions that are basically healthy. America’s racial arrangements are fundamentally unjust. To be conservative on racial matters is a moral crime. American conservatives never wrapped their mind around this. My beloved mentor, William F. Buckley Jr., made an ass of himself in his 1965 Cambridge debate against James Baldwin. By the time I worked at National Review, 20 years later, explicit racism was not evident in the office, but racial issues were generally overlooked and the GOP’s flirtation with racist dog whistles was casually tolerated. When you ignore a cancer, it tends to metastasize.

Mindar: It thrills me to no end to read Brooks words admitting that conservatives have never fully dealt with America’s sin of racism. The way that Republicans have traditionally addressed racism has never sat well with me, even when I was a straight-line voting Republican. Sadly, things have only gotten worse. In the early years of my involvement with the Republican Party, the racism was subtle and indirect. Today, Republicans are only all too happy to spew their racist hate openly and unapologetically. In this way, Republicans have been successful in taking us back to a time that may have been good for white males, but not so great for anyone else.

Brooks: Second, economics. Conservatism is essentially an explanation of how communities produce wisdom and virtue. During the late 20th century, both the left and the right valorized the liberated individual over the enmeshed community. On the right, that meant less Edmund Burke, more Milton Friedman. The right’s focus shifted from wisdom and ethics to self-interest and economic growth. As George F. Will noted in 1984, an imbalance emerged between the “political order’s meticulous concern for material well-being and its fastidious withdrawal from concern for the inner lives and moral character of citizens.” The purpose of the right became maximum individual freedom, and especially economic freedom, without much of a view of what that freedom was for, nor much concern for what held societies together.

Mindar: MAGA Republicans love to talk about freedom. But their freedom is an immature, juvenile freedom that knows neither responsibility nor obligation. It is the freedom of a four-year-old that wants what they want when they want it, and to hell with everyone else. The truth is, there is no freedom—not true freedom—without responsibility. Without responsibility, freedom becomes selfishness, chaos, a moral adolescence that rejects community in favor of the self-centered me. It is an un-American type of freedom that defies the values that built the country. And it is a freedom that rejects the most basic tenets of conservatism.

Brooks: But perhaps the biggest reason for conservatism’s decay into Trumpism was spiritual. The British and American strains of conservatism were built on a foundation of national confidence. If Britain was a tiny island nation that once bestrode the world, “nothing in all history had ever succeeded like America, and every American knew it,” as the historian Henry Steele Commager put it in 1950. For centuries, American and British conservatives were grateful to have inherited such glorious legacies, knew that there were sacred things to be preserved in each national tradition, and understood that social change had to unfold within the existing guardrails of what already was.

By 2016, that confidence was in tatters. Communities were falling apart, families were breaking up, America was fragmenting. Whole regions had been left behind, and many elite institutions had shifted sharply left and driven conservatives from their ranks. Social media had instigated a brutal war of all against all, social trust was cratering, and the leadership class was growing more isolated, imperious, and condescending. “Morning in America” had given way to “American carnage” and a sense of perpetual threat.

I wish I could say that what Trump represents has nothing to do with conservatism, rightly understood. But as we saw with Enoch Powell, a pessimistic shadow conservatism has always lurked in the darkness, haunting the more optimistic, confident one. The message this shadow conservatism conveys is the one that Trump successfully embraced in 2016: Evil outsiders are coming to get us. But in at least one way, Trumpism is truly anti-conservative. Both Burkean conservatism and Lockean liberalism were trying to find ways to gentle the human condition, to help society settle differences without resort to authoritarianism and violence. Trumpism is pre-Enlightenment. Trumpian authoritarianism doesn’t renounce holy war; it embraces holy war, assumes it is permanent, in fact seeks to make it so. In the Trumpian world, disputes are settled by raw power and intimidation. The Trumpian epistemology is to be anti-epistemology, to call into question the whole idea of truth, to utter whatever lie will help you get attention and power. Trumpism looks at the tender sentiments of sympathy as weakness. Might makes right.

Mindar: The party of “alernatve facts” has disconnected itself from reality. In it’s place, they have erected a world based on lies, and their adherents have tacitly agreed to accept those lies as truth. Their preferred TV outlet, Fox News, has paid out over $1 billion in lawsuits over the past year alone because of their incessant lying, yet they continue to push lies and half-truths to mollify their viewers and keep them uninformed and in the fold. Since 2016, MAGA Republicans have built an entire eco-system where up is down and black is white.

A MAGA friend of mine once told me that he lives in a red world. When I asked him to explain, he said that he only watches right-leaning news, only reads right-leaning newspapers, magazines, and websites, and only socializes with his fellow right-leaning MAGA friends. He lives in a silo and isn’t interested in having his mind changed. I found this so sad. Why would anyone intentionally subject themselves to such a limited view of the world. I don’t think he believed he was being lied to, but he had to know that he was restricting his information intake to such a degree that he was an easy mark to be lied to. To me, it seems like a horrible way to live. But I suspect he was happy living that way, ignorant to the truth, but comfortable in his ignorance.

Brooks: On the right, especially among the young, the populist and nationalist forces are rising. All of life is seen as an incessant class struggle between oligarchic elites and the common volk. History is a culture-war death match. Today’s mass-market, pre-Enlightenment authoritarianism is not grateful for the inherited order but sees menace pervading it: You’ve been cheated. The system is rigged against you. Good people are dupes. Conspiracists are trying to screw you. Expertise is bogus. Doom is just around the corner. I alone can save us.

What’s a Burkean conservative to do? A lot of my friends are trying to reclaim the GOP and make it a conservative party once again. I cheer them on. America needs two responsible parties. But I am skeptical that the GOP is going to be home to the kind of conservatism I admire anytime soon.

Mindar: The Republican Party is a mere shell of its former self. Sadly, it does not appear that this will change any time soon, if ever.

Brooks: Trumpian Republicanism plunders, degrades, and erodes institutions for the sake of personal aggrandizement. The Trumpian cause is held together by hatred of the Other. Because Trumpians live in a state of perpetual war, they need to continually invent existential foes—critical race theory, nongendered bathrooms, out-of-control immigration. They need to treat half the country, metropolitan America, as a moral cancer, and view the cultural and demographic changes of the past 50 years as an alien invasion. Yet pluralism is one of America’s oldest traditions; to conserve America, you have to love pluralism. As long as the warrior ethos dominates the GOP, brutality will be admired over benevolence, propaganda over discourse, confrontation over conservatism, dehumanization over dignity. A movement that has more affection for Viktor Orbán’s Hungary than for New York’s Central Park is neither conservative nor American. This is barren ground for anyone trying to plant Burkean seedlings.

I’m content, as my hero Isaiah Berlin put it, to plant myself instead on the rightward edge of the leftward tendency—in the more promising soil of the moderate wing of the Democratic Party. If its progressive wing sometimes seems to have learned nothing from the failures of government and to promote cultural stances that divide Americans, at least the party as a whole knows what year it is. In 1980, the core problem of the age was statism, in the form of communism abroad and sclerotic, dynamism-sapping bureaucracies at home. In 2021, the core threat is social decay. The danger we should be most concerned with lies in family and community breakdown, which leaves teenagers adrift and depressed, adults addicted and isolated. It lies in poisonous levels of social distrust, in deepening economic and persisting racial disparities that undermine the very goodness of America—in political tribalism that makes government impossible.

Mindar: While I agree with most of what Brooks has written in the preceding paragraphs, I can’t help but notice that he once again demonizes government writ large. Naturally, there are government failures that can be pointed to, but that doesn’t mean that government is bad. We need to move away from this idea that only a small, barely effective government is the goal.

Government in the United States needs to be improved, not abandoned or shrunk beyond recognition. We are a large, sprawling, diverse country with a plethora of needs. It can be easy to say that “the church should solve that problem,” or “that challenge should be addressed by the local community.” The government—whether federal, state, or local—is the best positioned organization to handle most of the country’s needs, and we need to get over this idea that the government either shouldn’t or isn’t capable of improving the lives of its citizens.

Brooks: There is nothing intrinsically anti-government in Burkean conservatism. “It is perhaps marvelous that people who preach disdain for government can consider themselves the intellectual descendants of Burke, the author of a celebration of the state,” George F. Will once wrote. To reduce the economic chasm that separates class from class, to ease the financial anxiety that renders life unstable for many people, to support parenting so that children can grow up with more stability—these are the goals of a party committed to ameliorating, not exploiting, a growing sense of hopelessness and alienation, of vanishing opportunity. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s brilliant dictum—which builds on a Burkean wisdom forged in a world of animosity and corrosive flux—has never been more worth heeding than it is now: The central conservative truth is that culture matters most; the central liberal truth is that politics can change culture.

Mindar: Yes, this is what I was just saying. Conservatism has morphed into an anti-government philosophy. But Burkean conservatism doesn’t preach an anti-government sermon. Sadly, today, those that call themselves conservatives are rarely conservative. If American conservatism isn’t dead, it is badly wounded, and it’s prognosis is quite grave.

Have you ever had a complete stranger change your life? It happened to me, and I want to share the story of how it happened. It’s a story I’ve never told, but one that I think is important.

Have you ever had a complete stranger change your life? It happened to me, and I want to share the story of how it happened. It’s a story I’ve never told, but one that I think is important.

The Union won the war, at least in theory. The Confederate Army was defeated, but the southern states carried on as if they hadn’t lost. Confederate officials continued to run things in the south, and black Americans, now freed from bondage—again, in theory—continued to be mistreated and denied their Constitutional rights. Lincoln had a plan to free the slaves, but how he planned to incorporate them into the larger society was murky at best. Then, he was assassinated.

The Union won the war, at least in theory. The Confederate Army was defeated, but the southern states carried on as if they hadn’t lost. Confederate officials continued to run things in the south, and black Americans, now freed from bondage—again, in theory—continued to be mistreated and denied their Constitutional rights. Lincoln had a plan to free the slaves, but how he planned to incorporate them into the larger society was murky at best. Then, he was assassinated. A little over a year ago, I published a post entitled

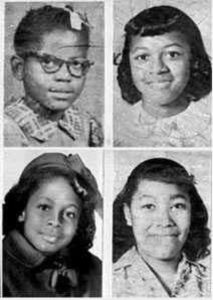

A little over a year ago, I published a post entitled  Today marks the 60th anniversary of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama and the death of four young black girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Carol Denise McNair. Birmingham was no stranger to bombings. Between 1947 and 1965 there for fifty separate bombings of homes, businesses, and churches in the town that came to be known as “Bombingham.”

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama and the death of four young black girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Carol Denise McNair. Birmingham was no stranger to bombings. Between 1947 and 1965 there for fifty separate bombings of homes, businesses, and churches in the town that came to be known as “Bombingham.” Dan Buettner is a National Geographic Fellow and a best-selling author who has devoted much of his life to understanding why some communities produce large numbers of people who live to be 100 years of age or older. These communities, known as Blue Zones, are spread throughout the world, and although they are disparate geographically, they seem to have several things in common that lead their residents to live to 100 and beyond.

Dan Buettner is a National Geographic Fellow and a best-selling author who has devoted much of his life to understanding why some communities produce large numbers of people who live to be 100 years of age or older. These communities, known as Blue Zones, are spread throughout the world, and although they are disparate geographically, they seem to have several things in common that lead their residents to live to 100 and beyond. This post was originally published on February 19, 2020.

This post was originally published on February 19, 2020. Politically speaking, I came of age in 1980. That year, I worked on the campaign of presidential candidate John Anderson, an Illinois Congressman who was running as an independent. To be honest, my motives working for the campaign were a bit misdirected. I was chasing a girl who worked on the campaign. Anderson won 6.6% of the vote. I did significantly worse.

Politically speaking, I came of age in 1980. That year, I worked on the campaign of presidential candidate John Anderson, an Illinois Congressman who was running as an independent. To be honest, my motives working for the campaign were a bit misdirected. I was chasing a girl who worked on the campaign. Anderson won 6.6% of the vote. I did significantly worse.