This is part 2 of the Saving the Court series. I would encourage you to read previous posts, including:

In this post, I’ll examine how we got into the situation we find ourselves in today. It started several years ago, and has only gotten worse over time.

——————–

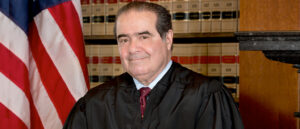

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died in his sleep on February 13, 2016, at the Cibolo Creek Ranch in Shafter, Texas. Scalia was at the ranch at the invitation of John Poindexter, a businessman and owner of the ranch, to hunt quail. The arrangement was a bit unusual. One of Poindexter’s subsidiary companies, the Mic Group, had recently been before the Supreme Court in an age discrimination case. The Court had denied certiorari, securing the Mic Group’s victory in the lower court.

Scalia’s death set off a chain of explosive events that transformed the Supreme Court over the following four years and raised calls for Court reform. But it was not the ethical implications of Scalia’s death that led to the upheaval. Instead, it was the actions taken by the Senate in the aftermath of the Justice’s death that reconfigured and set off a political firestorm that still rages today.

When Scalia died, President Barack Obama had just begun the final year of his second term in office. The 2016 Presidential Election was nearly nine months away, and Obama’s term would not end for another eleven months. Obama nominated Merrick Garland, a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, to replace Scalia. Garland was considered a centrist, and he was well-respected in legal circles, having received the American Bar Association’s highest rating.

By all accounts, Garland was about as good a nominee as the Republicans in the Senate could have hoped for from a Democratic President. He was not the extreme liberal some had feared. Even so, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) notified President Obama that the Senate would not take up the nomination of Garland. His public justification for refusing to hold hearings on Garland’s nomination was that voters should have a voice in who is nominated to the nation’s highest court by casting their ballot in the upcoming Presidential Election. Privately, McConnell knew that no one could force him to consider Garland’s nomination. For him, that was justification enough.

Article II, § 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution gives the President the power to appoint Justices of the Supreme Court, with the advice and consent of the Senate. Traditionally, even if the majority party in the Senate was not in favor of a nominee, they would carry out their “advise and consent” duty. What McConnell did in refusing to even consider the President’s nomination so far in advance of the next Presidential Election was unprecedented. Democrats screamed foul, and the President continued to push his nominee. McConnell was unmoved. He knew that neither the President nor Democrats in the Senate could force him into scheduling hearings on Garland’s nomination.

McConnell waited out Obama, and in November 2016, Donald J. Trump was elected President. Less than a month into his first year in office, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, a conservative jurist serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth District, to replace Scalia. Although many Democrats voted against Gorsuch because they felt Garland was the rightful nominee, Trump’s nominee was nonetheless approved 54-45 by the Senate.

When Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement in June 2018, Trump had the opportunity to appoint another Justice to the Supreme Court. This time he selected Brett Kavanaugh, a judge serving on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing turned into a spectacle. College Professor Christine Blasey Ford accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her in 1982 when they were both in high school. Democrats lamented the White House’s refusal to provide hundreds of thousands of documents pertinent to Kavanaugh’s record, and complained that the Department of Justice failed to fully investigate charges leveled against Kavanaugh. Protesters interrupted the proceedings screaming “Women’s rights are human rights” and “Protect women, be a hero.” As for Kavanaugh, he adamantly defended himself from sexual assault charges, and unequivocally confessed his love for beer. Even by modern day standards, the hearing was highly charged and highly partisan. In the end, Kavanaugh was confirmed, and Republicans added another conservative to the Court.

With Neil Gorsuch replacing Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court saw one conservative Justice replace another. Kavanaugh’s replacement of Kennedy was a little different. Kennedy was a swing vote, sometimes siding with conservatives, sometimes with the liberal wing of the Court. Kavanaugh, on the other hand, has proven to be a reliable conservative vote. To Democrats’ dismay and Republicans’ joy, the Court was becoming more conservative.

Then, on September 18, 2020, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died following a long battle with cancer. The diminutive Ginsburg was a liberal titan known for her fiery dissenting opinions. Her death was a worst-case scenario for Democrats and liberal Court watchers. For years, they had hoped, even encouraged, Ginsburg to retire so President Obama could appoint a replacement. Their fear was that Ginsburg, who was elderly and in failing health, would die during a Republican administration, allowing the President to replace her with a conservative Justice.

Of course, Democrats’ worst fears were realized when Ginsburg passed away during the waning days of the Trump Administration. When she died, the 2020 Presidential Election was less than two months away. Polls were not looking good for President Trump, and Republicans feared he would lose the November election. Of course, Mitch McConnell had set a precedent in 2016 when he refused to hold confirmation hearings on Merrick Garland, Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, because a Presidential Election was coming up later that same year. Now, there were less than two months until the election.

It did not matter. As mourners gathered to pay tribute to Ginsburg on the evening of her death, and President Trump was on Air Force One returning from a campaign rally in Minnesota, McConnell sprang into action. He contacted the President to inform him that the Senator would be issuing a statement announcing Ginsburg’s seat would be filled as quickly as possible, and he encouraged the President to nominate Amy Coney Barrett.

Democrats were apoplectic. How could McConnell agree to hold hearings on a Supreme Court nominee less than two months before an election, especially after how he justified not holding hearings on Garland? McConnell absorbed the accusations of hypocrisy and moved forward with the confirmation hearings. Barrett was confirmed and the Supreme Court stood at six conservative and three liberal Justices. At a time when national politics were moving leftward and voters were about to elect a Democrat to the White House by an overwhelming margin, the Supreme Court was solidly conservative, and it appeared it would remain that way for years to come.

This phenomenon—society moving left while the Supreme Court moves right—does not bode well for the future. When voters hold one set of political beliefs while the highest court in the land rules based on a different, even opposite, set of beliefs, the Supreme Court loses its legitimacy.

To put a slightly finer point on this idea that popular opinion is moving in an opposite direction from the opinion of the Court, it is important to remember that five of the six conservative Justices (Roberts and Alito appointed by George W. Bush, and Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett appointed by Donald J. Trump) were appointed by Presidents who lost the popular vote. Additionally, four of the six conservative Justices (Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett) were confirmed by Senators who combined, represented less than half of the U.S. population.

To make matters worse, the confirmation process for Supreme Court Justices has become completely dysfunctional. It was not that long ago that confirmation of a President’s Supreme Court nominee, except in rare instances, was a given. It was common for Senators from both parties to support the nominee to the Court. In recent years, the opposite has been true. Drama routinely surrounds the nomination, and the confirmation vote is more often than not played out along party lines.

Charges of judges “playing politics” and staying beyond their most productive years have also been leveled. Prominent scholars accuse Supreme Court Justices of naked partisanship, and they caution that the Court is turning into a “supreme gerontocracy,” where members stay on the bench into their years of “mental decrepitude.”

All of these issues add up to a Court that is experiencing a crisis of legitimacy. But is the legitimacy crisis aimed at the Supreme Court writ large or is it a crisis that only afflicts the current makeup of the Court?

I think it is fair to say that the Supreme Court as an institution enjoys wide-spread support; what is often referred to as diffuse support. Generally speaking, Americans like having a high court that makes final decisions on legal issues.

In fact, Judge Irving Kaufman wrote an essay in 1984 that spoke to the public’s willingness to accept and honor Court decisions, even when they disagree with those decisions, provided the Court’s decision makes it clear that the majority was acting in good faith. “When, in the public mind, the Court is functioning as an apolitical, wise and impartial tribunal, the people of our nation – even those citizens to whom the results may be anathema – have evinced a willingness to abide by its decisions.” What goes unsaid is that the public will not accept and honor decisions made by the Court that are political, unwise, or partisan in nature. That appears to be where we are with today’s Court.

So, we’re dealing with a Court that, as an institution, enjoys wide support from the American public. But the make up of this particular Court–the individual Justices as opposed to the institution–is currently experiencing record high disapproval ratings.

What’s to be done? Most observers agree that some reforms need to be made to the Court. Of course, there is a wide disparity of opinion about which reforms should be implemented. In the coming weeks, I’ll examine the various reform proposals and do my best to determine which will help restore the Court’s legitimacy, and which won’t. As I do, I will do my best to keep two caveats in mind:

Caveat #1: Don’t Let Perfect Be the Enemy of Good

All too often, analysis of proposals to reform the Supreme Court are focused more on the problems with those proposals than with the problems that already exist with the Court. To be certain, it is important to examine the pros and cons of any proposal, but it is equally important to recognize that the Supreme Court currently suffers from serious issues. We cannot fix those problems if we hold out for the perfect solution. The truth is, there are no solutions—no reform proposals—that do not suffer from issues of their own. If there were, we would have implemented them long ago. None of the reform proposals examined herein come without a downside. Even so, I will endeavor to judge these proposals on their merits rather than dismissing them because they are not perfect solutions.

Caveat #2: Supreme Court Decisions Are Not Divinely Inspired

Let me offer one further caveat. The Supreme Court is often viewed as sacrosanct. The Presidency and Congress are obviously political. They both often ooze partisanship. Not so with the Supreme Court, at least not on the surface. We want to view the Supreme Court as being above the partisan fray, and we want to view their decisions as above reproach. Sadly, neither is true.

First, although Supreme Court Justices are not elected, they are nominated and confirmed as part of a political process. The political leanings of the Justices are very much germane to whether or not they get nominated and confirmed. Granted, the politics of the individual members of the Court are normally not out on display for everyone to see, but their political beliefs still play an important role in the job they do on the Court.

Second, Justices of the Supreme Court are human. Like anyone else, they have their flaws and foibles, their strengths and weaknesses. We would like to think that their decisions are infallible, but they are not. As Justice Scalia famously said in Cruzan v. Missouri Department of Health (497 U.S. 261) (1990) (Scalia, J. , concurring), “nine people picked at random from the Kansas City telephone directory” are no less all-knowing or insightful than the Justices of the Supreme Court.

To put it another way, Supreme Court decisions are not divinely inspired. They are the work of human beings who do the best they can, but often fall short. Members are not omnipotent, and we should not expect them to be. However, we should endeavor to structure the Court and implement policies for it that get us as close to omnipotence as possible, recognizing that we will never fully realize that goal.

Before jumping into the various reform proposals, in the next post, I want to spend some time reviewing the history of Supreme Court reform efforts to better understand what reforms have been tried before, and what might be possible in the future.