In an earlier post, I confessed my love for the HBO series, Deadwood. The series was near-perfect, in both character development and storytelling. One of the things I noted about the show in that earlier post was that almost everything about the show felt realistic. What I meant by that was that the people running Deadwood never strayed too far outside the bounds of history and believability. Many of the characters were real. They had actually lived and participated in the early days of Deadwood and the Dakota Territory.

In an earlier post, I confessed my love for the HBO series, Deadwood. The series was near-perfect, in both character development and storytelling. One of the things I noted about the show in that earlier post was that almost everything about the show felt realistic. What I meant by that was that the people running Deadwood never strayed too far outside the bounds of history and believability. Many of the characters were real. They had actually lived and participated in the early days of Deadwood and the Dakota Territory.

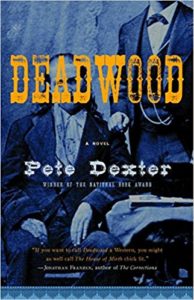

Many years ago, I read a novel entitled Deadwood by Pete Dexter (published in 1986). Like the HBO series, Dexter’s novel was gritty and realistic. After watching the series for a second time, I re-read Dexter’s book. I liked it just as much as I did the first time (five stars on Goodreads), but I noticed differences, both big and small, between the book and the TV show.

I often wondered if David Milch and the creators of the HBO show used Dexter’s book as research or inspiration. I had the good fortune to have a Twitter conversation about this with W. Earl Brown, the actor who played Dan Dority, and is a continuing promoter of the HBO series. He was not only an actor, he also was a writer on the show, earning a Writers Guild of America Award nomination in the process.

Brown indicated that after securing his role, he purchased a copy of Dexter’s book. However, before he could read it, David Milch encouraged everyone involved with the show not to read any works of fiction related to Deadwood. Milch said he didn’t want other’s fiction to subliminally guide the work they were doing on the show. Brown commented that enough time has passed now, and he’d like to read the book.

***

Fun Fact: W. Earl Brown received an MFA in Acting from The Theater School at DePaul University.

His classmates included John C. Reilly and Gillian Anderson.

***

One of the things that interests me most about Deadwood—both the show and the book—is who was real and who wasn’t. And of those characters that were real, how accurate the portrayal was compared to their real lives.

For instance, we know that Wild Bill Hickok was a real person. He was born James Butler Hickok in 1837 in Homer, Illinois, about a hundred miles west-southwest of Chicago. Since then, the town has been renamed Troy Grove. He left Illinois at the age of 18 after a getting into a fight with a man named Charles Hudson. He mistakenly thought he had killed Hudson and hightailed it to Kansas to avoid arrest.

He took on his brother’s name, “William”—presumably while running from the law—and gave himself the nickname “Wild Bill.” The reason he gave himself a nickname was because he didn’t like the nicknames others gave him. For instance, he had been called “Duck Bill” because of his long nose and protruding lips. He had also been called “Shanghai Bill” because of his height and slim build.

In March 1876, Hickok married Agnes Thatcher Lake, a circus proprietor eleven years his senior. A few months later he departed for Deadwood. He had been diagnosed with glaucoma shortly before marrying, and he was going to Deadwood for the supposed purpose of staking a gold claim.

Hickok arrived in Deadwood as part of Charlie Utter’s wagon train in July 1876. Also on that wagon train was Martha Jane Cannery, better known as Calamity Jane. Rather than working to stake a claim, Bill spent his time gambling.

On August 1, 1876, Bill was playing poker at Nuttal & Mann’s Saloon No. 10. Also at the table was a man by the name of Jack McCall. Bill won a lot of money from McCall that day, and when McCall, drunk and dejected, quit the game, Bill offered him enough money to get breakfast. McCall took the money, but was insulted that Bill treated him like a charity case.

The following day, Bill was again at Nuttal & Mann’s, but his usual seat was taken, so he sat in another chair with his back to the room. He didn’t see McCall enter the bar, come up behind him, and point a gun at his head. McCall screamed, “Damn you! Take that!” and shot Bill in the back of the head, killing him instantly. At the time of his death, Bill was holding two pair, eights and aces. Since then, that hand has been known as “dead man’s hand.”

In the HBO show, they stick pretty close to the actual story, although they exaggerated the number and intensity of the interactions between Hickok and McCall. The book takes a different tact. Dexter ignored the true story and had McCall kill Hickok at the behest of someone else.

In both the book and the TV show, Bill writes a letter to his wife shortly before his death. In the letter, he writes, “Agnes Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife—Agnes—and with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore.” According to the book, Famous Last Words by Laura Ward, Bill, in fact, did write those words in a letter to his wife shortly before his death.

Because of this letter, and the fact that Bill uncharacteristically sat with his back to the room, some historians posit that Bill was suicidal, inviting someone to shoot him. They argue that, because of his worsening glaucoma, Bill could not stomach the thought of being dependent on others to see for him. In addition, the glaucoma took away his only two ways of making a living, shooting and playing cards.

Although the HBO series stuck to the storyline of Bill losing his eyesight, the Dexter book intimated that, in addition to failing eyesight, Bill had prostate problems and/or venereal disease, although Dexter never called it that. Instead, Bill went to a doctor for a “blood disease” that effected his urinary tract, making it difficult to urinate. The cure prescribed to him was mercury, rubbed liberally over his body. Of course, we know now that mercury causes illness, it doesn’t cure it. The treatment sounds horrible, potentially worse than the disease, but it appears that Bill didn’t suffer this fate in real life.

Little is known about Hickok’s assassin, Jack McCall. He was born in the 1850s in Kentucky, and eventually moved west to hunt buffalo. In the show, McCall was a degenerate gambler and drunk. In the book, he was a cat wrangler, working for a business that rented cats to people with rat or mouse problems. McCall was the one who rounded up the cats and delivered them to customers. In both the show and the book, McCall was mentally weak, if not brain damaged. In real life, he was cowardly, but there’s no indication he was mentally challenged.

After shooting Hickok, McCall was tried by an impromptu court in Deadwood and found not guilty. He claimed that he had shot Hickok as revenge for Hickok shooting his brother. However, records indicate that McCall did not have a brother. He left Deadwood and relocated to the Wyoming Territory, where he bragged about killing Hickok. Unfortunately for him, Wyoming authorities arrested him again, claiming that the court in Deadwood didn’t have jurisdiction. McCall was transferred to Yankton, South Dakota where he was convicted of murder. In March 1877, Wild Bill’s killer was hanged.

In the HBO show, Seth Bullock and Charlie Utter set out after McCall when he flees Deadwood following his acquittal in the first trial. However, that’s not how it happened. To be sure, Hickok and Utter were friends. At the time of Hickok’s murder, Utter was out of town. In the book, he had traveled to Cheyenne to challenge the current pony express company to a race in a bid to take over their business. Utter wins the race, but, heartbroken over Wild Bill’s death, he never does start up a delivery company.

In the HBO show, again, Utter is in Cheyenne competing for the pony express business. When he returns, after avenging Bill’s murder, he starts a delivery company.

As for Bullock, it’s unlikely he ever really met Hickok in real life. He arrived in camp on August 1, 1876 and Hickock was killed the very next day. The TV show portrayed a mutual respect and budding friendship between Bullock and Hickok before the latter’s death. In the book, Bullock and Hickok met in passing, but there was very little interaction between them.

The real Seth Bullock was an interesting guy. He was born in Canada in 1849 and moved to Montana in 1865 to live with his sister. He was elected sheriff of Louis and Clark County, Montana where he engaged in a gun battle with a horse thief named Clell Watson. Bullock took a bullet to the shoulder, but successfully apprehended the horse thief. Watson was scheduled to be hanged, but a mob showed up in support of Watson and drove away the executioner. Bullock fought off the mob with a shotgun and carried out the hanging himself. This incident is very similar to an incident portrayed in the TV show, except it happened years later in Deadwood. The book did not mention Bullock’s life before Deadwood.

***

Fun Fact: While serving in the Montana Territorial Legislature, Seth Bullock helped create Yellowstone National Park

***

Bullock and his friend, Sol Star, opened a hardware store in Helena, but soon decided their fortunes lie in the Black Hills of South Dakota where there was a gold rush taking place. They arrived in Deadwood in August 1876, bought a lot, and started “Star and Bullock, Auctioneers and Commission Merchants,” first in a tent, then in a building. In the book, Star and Bullock own a brick making business, but in reality, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

The TV show portrayed Bullock as a reluctant sheriff. However, law enforcement was his chosen profession. And, despite all the gunplay in both the show and the book, Bullock never killed anyone as sheriff, although he did have several run-ins with Al Swearengen, the owner of the Gem Theater. Unlike in the HBO series, Bullock was not the sheriff of Deadwood, but instead was appointed the first sheriff of Lawrence County, South Dakota.

In the HBO show, Bullock married his dead brother’s wife, Martha, as an act of mercy. She and the dead Bullock had a son named William. Shortly after arriving in Deadwood, William is killed by a stampeding horse. In real life, although Bullock was married to a woman named Martha, the rest of the TV portrayal is fiction. There was no dead brother, no widow wife, and no son (at least at that time). When Martha Eccles Bullock arrived in camp, she brought with her a daughter. Subsequently, she and Seth had another daughter, and a son.

***

Fun Fact: Seth Bullock and Martha Eccles Bullock were childhood sweethearts

***

Bullock wasn’t just sheriff of Lawrence County. He had several business interests. In addition to Star and Bullock, Auctioneers and Commission Merchants, they also owned a cattle operation dubbed S&B Ranch Company, as well as Deadwood Flour Milling. When the building that housed their hardware business burned down in 1894, rather than rebuild, they erected the town’s first luxury hotel, called the Bullock Hotel (which is still in operation today).

Bullock met Theodore Roosevelt in 1884 and the two became fast friends. Bullock joined Grigsby’s Cowboy Regiment in 1898 to support Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. However, the war ended before Grigsby’s Cowboy Regiment could be deployed. For his efforts, Bullock earned the rank of captain. When Roosevelt became vice-president under William McKinley, Bullock was named the first forest supervisor of the Black Hills Reserve. When Roosevelt became president in 1905, Bullock participated in his friend’s inaugural parade. The new president then named Bullock U.S. Marshal for South Dakota. Bullock was one of 18 officers selected by Roosevelt to gather recruits for Roosevelt’s World War I Volunteers.

After Roosevelt’s death, Bullock created a monument to his friend on Sheep Mountain. He also led the efforts to rename the mountain “Mount Roosevelt.” Bullock died of colon cancer in 1919 and is buried near Wild Bill and Calamity Jane in Mt. Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood.

***

Fun Fact: Seth Bullock is credited with introducing alfalfa farming to South Dakota

***

Pete Dexter’s book, Deadwood, focuses primarily (although not exclusively) on Charlie Utter. He was born in 1838 in Niagara Falls, New York, and was raised in Illinois. He eventually made his way to Colorado in the 1860s where he got the nickname “Colorado Charlie.” He worked as a trapper, a guide, and a prospector, before forming his own wagon train in 1876 with his brother, Steve, and heading off for Deadwood.

Utter was known as a snappy dresser, unusual at that time, and the opposite of how he was portrayed in the HBO series. He also had the rather odd habit of bathing every day, which was included in the Dexter book. Utter insisted on sleeping under only the highest quality blankets, he was very particular about his hair, and he didn’t allow anyone—not even Wild Bill—into his tent.

Just as in the TV show, Utter started a lucrative delivery business, shuttling mail and freight between Deadwood and Cheyenne. However, his business was short lived. In early 1879, he purchased a saloon in Gayville, South Dakota When things didn’t work out the way he had hoped, he returned to Deadwood just in time to watch fire destroy the town on September 26, 1879.

After the fire, Utter returned to Colorado for a time, then went to Socorro, New Mexico, where he opened another saloon. It’s not clear when he left New Mexico, but he ended up in Panama, where he owned drugstores in Panama City and Colon. Utter went blind and was not heard from again after 1913. It is believed that he died in Panama.

In Deadwood: The Movie, Utter is killed by an assassin hired by George Hearst. Hearst wanted a parcel of land that Utter owned, but Utter refused to sell. This is fiction. While it is true that George Hearst and Charlie Utter were in Deadwood at the same time (from October 1877 to September 1879), it is unknown if their paths crossed. Dexter’s book ends with Utter in Panama, whiling away his days in the sun.

One of the main characters in the TV show was Al Swearengen. In the show, he was English-born. As a child, Al moved to Chicago with his mother, who was a prostitute. When she left town, Al was placed in an orphanage, where the head mistress rented him out to pedophiles. This was all fiction. In fact, in real life, Al was one of eight children (along with his twin brother, Lemuel) born to a Dutch-American couple in Oskaloosa, Iowa in 1845. He remained in Iowa until 1876, when he relocated to Deadwood.

Upon arriving in camp, Al started the Cricket Saloon. It was housed in a canvas and lumber building, and featured gambling and prizefights. The Cricket did great business and Al need a bigger place. So, he started the Gem Theater in a proper building. The Gem was a saloon, dance hall, and brothel, the latter of which earned Al the reputation of being a brutal pimp. He would advertise jobs in hotels–such as maids, clerks, and entertainers–to recruit women. Those that responded were given a one-way ticket to Deadwood, where they would find themselves stranded and at the mercy of Swearengen. They were given the choice of either becoming prostitutes or being left to die in the street. Those that chose to become prostitutes were physically abused to keep them in line.

Unlike the character on the TV show, the real Al was married three times. His first wife, Nettie, followed him to Deadwood, but soon divorced him, claiming spousal abuse. He married two more times with the same results.

In Dexter’s book, Swearengen is in hiding from an assailant when he asks his wife to collect his money from the bank so he can flee. Instead, his wife collects the money and she flees, both her husband and Deadwood.

In real life, Swearengen made a fortune from the Gem, earning $5000-$10,000 most nights. However, it wasn’t without its challenges. The Gem burned down in September 1879. He rebuilt, only to have his business burn down again in 1899. By that time, Swearengen had had enough of Deadwood. He relocated to Denver.

In Deadwood: The Movie, a sequel to the HBO show, Al is shown as a weakened and dying man in 1889. This wasn’t clear to me, but it appeared that he died in his room above the Gem at the end of the film, leaving the Gem Theater to Trixie, his favorite prostitute.

Swearengen is portrayed much differently in the book. Dexter makes him out to be a brutal, bi-sexual whoremonger who is shot and killed by Charlie Utter.

Of course, neither the movie nor the book are factual. In real life, Al moved to Denver in 1899. In November 1904, he was found dead in the street. The cause of death was blunt force trauma to the head. Was it murder? He could have fallen and hit his head, but authorities at the time believed he was struck on the head by an assailant while trying to hop a train. Despite the money he made at The Gem, Swearengen died penniless.

***

Fun Fact: Much of the action in the first season of the HBO show Deadwood takes place in 1876 at

Al Swearengen’s Gem Theater. However, in real life, The Gem did not open until 1877.

***

To be continued in Part 2…