Things were very different back in 1968. The war in Vietnam was raging, civil rights protests across the United States were at their zenith, and people got their news from one of three television networks or their local newspaper.

The daily newspaper was a big deal. For five cents a day (twenty-five cents on Sunday), you could find out what was going on around your town and around the world. You could also get a laugh reading the newspaper. Nearly every local newspaper included syndicated comic strips. During the week, the comics were printed in black & white. But on Sundays, they were printed in color and had their own pull out section.

Some of the more popular comics were Beetle Bailey, Marmaduke, Dennis the Menace, and the Katzenjammer Kids. Perhaps the most popular comic of all time was Peanuts. Even back in 1968, everyone knew the characters like Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Lucy, Linus, and the rest of the gang. Over time, Peanuts morphed into an international brand, being adapted into TV shows and movies, and selling a ton of merchandise.

That same year of 1968 also saw a great deal of tragedy. In April of that year, civil rights leader, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was gunned down as he stood on the balcony of the motel where he was staying in Memphis, TN. The nation was shocked and saddened. No one more so that Los Angeles schoolteacher, Harriet Glickman. Glickman was a follower of MLK and believed that his nonviolent approach to protesting for civil rights was making headway. Even though President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 just one week after MLK’s death, Glickman feared that his murder would set back the civil rights movement.

“Glickman was disturbed by the racial upheaval that was shaking the country and wanted to do something about ‘the vast sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate, and violence’ that caused it. She believed that at a time when whites and blacks looked distrustfully at one another from across a wide racial divide, anything that could help narrow that gap could provide an immensely positive service to the nation.”

Glickman was also an avid reader of the Peanuts comic strip. Although she loved Charlie Brown and his pals, it bothered her that Peanuts did not contain any characters of color. So, on April 15–just eleven days after King’s murder and four days after Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968–Glickman wrote a letter to Charles Schultz, the creator of Peanuts.

Peanuts was read by millions of Americans every day. But since its creation in 1950, the Peanuts comic strip had never included a black character. Glickman felt that had to change. She hoped that by adding a black character, the cultural clout enjoyed by Peanuts could help to usher in a more positive relationship between whites and blacks in America.

In part, her letter to Schultz said:“

“It occurred to me today that the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters could happen with a minimum of impact. The gentleness of the kids … even Lucy, is a perfect setting …

“I’m sure one doesn’t make radical changes in so important an institution without a lot of shock waves from syndicates, clients, etc. You have, however, a stature and reputation which can withstand a great deal.”

Schultz was sympathetic with Glickman, but wasn’t sure if he was the right person to help Glickman or if Peanuts was the right vehicle to carry her message. In part, here is how he responded to Glickman:

“Dear Mrs. Glickman:

“Thank you very much for your kind letter. I appreciate your suggestion about introducing a Negro child into the comic strip, but I am faced with the same problem that other cartoonists are who wish to comply with your suggestion. We all would like very much to be able to do this, but each of us is afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends.

“I don’t know what the solution is.”

Rather than being discouraged, Glickman saw Schultz’s letter as a hopeful sign. She asked Schultz if he would mind if she shared his letter with some of her African-American friends to get their reaction.

Not only did Schultz not mind, he was excited to hear what Glickman’s friends had to say.

“I will be very anxious to hear what your friends think of my reasons for not including a Negro character in the strip. The more I think of the problem, the more I am convinced that it would be wrong for me to do so. I would be very happy to try, but I am sure that I would receive the sort of criticism that would make it appear as if I were doing this in a condescending manner.”

Glickman’s friends were excited at the prospect of having Schultz include a black character in his comic strip. They thought that it was important to see black people represented in a comic strip as popular as Peanuts. One African-American mother wrote:

“At this time in history, when Negro youths need a feeling of identity; the inclusion of a Negro character even occasionally in your comics would help these young people to feel it is a natural thing for Caucasian and Negro children to engage in dialogue.”

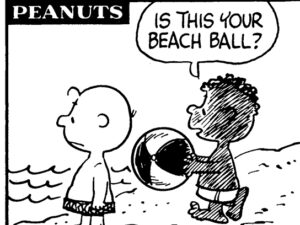

Schultz was pleased with the responses Glickman shared with him and told her that he might have a surprise for her in the July 29, 1968 comic strip. On that date, Charlie Brown went to the beach and met a young black character named Franklin.

Schultz did not pander when he introduced Franklin. There was no special announcement that a black character was being added to Peanuts. He didn’t make a big deal out of it at all. Other than his skin color, there was nothing different or special about Franklin. He was just a kid like Charlie Brown.

Glickman and her friends were thrilled with the introduction of Franklin. But not everyone was happy. Several readers wrote to Schultz and his syndicator, United Feature Syndicate. One letter said:

November 12, 1969

United Feature Syndicate

220 East 42nd Street

New York, N.Y. 10017

Gentlemen:

In today’s “Peanuts” comic strip Negro and white children are portrayed together in school.

School integration is a sensitive subject here, particularly at this time when our city and county schools are under court order for massive compulsory race mixing.

We would appreciate it if future “Peanuts” strips did not have this type of content.

Thank you.

Some Southern newspapers refused to carry the strips that included Franklin, which made United Features Syndicate nervous. The president of United Features Syndicate, Larry Rutman, asked Schultz to leave Franklin out of future strips, but Schultz wasn’t giving in. Schultz told Rutman, “Well Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it, or I quit. How’s that?”

Schultz had gone to great lengths not to jam Franklin down his readers’ throats. In fact, although Franklin was depicted as a black character, Schultz never discussed race in his comic strip. Franklin was simply one of the kids.

Around the same time Franklin was introduced in Peanuts, other cartoonists were taking a different tact concerning black characters. Allen Saunders, who wrote the Mary Worth comic strip, refused to include a black character for fear that “militant blacks” would protest his strip. On the other hand, Hank Ketchum, who wrote Dennis the Menace, included a black character in May 1970, but purposely modeled the character after Little Black Sambo, a racist cartoon from the 1930s.

Although Schultz’s depiction of Franklin was far more sensitive than some of his colleagues, he did not escape criticism from black readers. Some felt that Franklin was too perfect and didn’t suffer the same type of personality flaws as Schultz’s white characters. Franklin was intelligent and thoughtful, and he suffered far fewer anxieties or obsessions than the other characters. He also is the only character who doesn’t criticize or taunt Charlie Brown. Schultz did this on purpose to avoid the African-American tropes of the day and to make Franklin easier for readers–both white and black–to accept.

African-American columnist, Clarence Page, understood Schultz’s dilemma. In his Chicago Tribune column he wrote:

“Let’s face it: His perfection hampered Franklin’s character development…

“But considering the hyper-sensitivities so many people feel about any matters involving race, I did not blame Schulz for treating Franklin with a light and special touch.

“Can you imagine Franklin as, say, a fussbudget like Lucy? Or a thumb-sucking, security-blanket hugger like Linus? Or an idle dancer and dreamer like Snoopy? Or a walking dust storm like Pig Pen? Mercy. Self-declared image police would call for a boycott. If Schulz’s instincts told him his audience was not ready for a black child with the same complications his other characters endured, he probably was right.”

Franklin appeared on and off in the Peanuts comic strip for thirty years, until Schultz’s death in 1999. One person who was impacted by Franklin’s inclusion was Robb Armstrong, a young black aspiring cartoonist. When he got older, Armstrong met Schultz and the two became friends. As Schultz was working on a video that included Franklin, he realized that his character would need a last name. Schultz called Armstrong for permission to borrow his last name for Franklin. Armstrong agreed, and the rest is history.

Including Franklin in Peanuts was both a small thing and revolutionary. Schultz could have played it safe and stuck just with white characters. Instead, he not only made the hard decision to include Franklin, but did it in a way that neither relied on tropes nor “holier-than-thou” lectures. As a result, Franklin made an undeniable mark not only in comic strips, but in the wider culture, helping to usher in Glickman’s goal of changing the perceptions whites and blacks had of each other.

Merry Christmas, Franklin (and Schultz and Glickman)!